Flutter Training by Experts

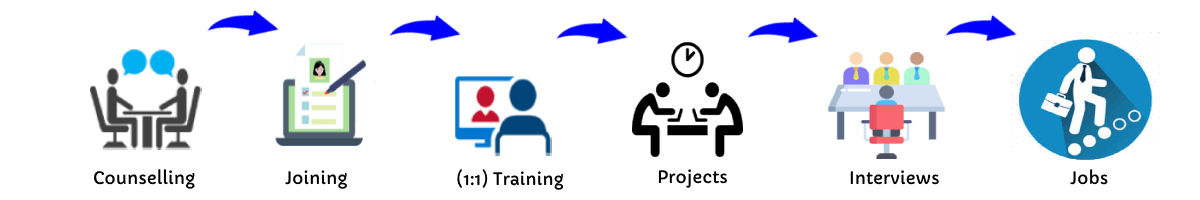

Our Training Process

Flutter - Syllabus, Fees & Duration

Module 1: Introduction

- Introduction to Flutter

Module 2: Introduction To Dart

- Reason why Dart holds the fort strong.

- Installing Visual Studio Code and the Dart Plugin.

- Installing Dart SDK.

- Writing the first Dart Program.

Module 3: Setting Up Flutter

- Downloading/Cloning the Flutter SDK.

- Installing Flutter Plugin within VS Code.

- Understanding the structure of a Flutter Project.

- Building a simple app from scratch.

Module 4: Introducing Widget

- Widgets and their role in a Flutter app.

- The MaterialApp and Scaffold widget.

- AppBar.

- FloatingActionButton.

- More widgets - Text, Center and Padding.

- Recreating the Default Flutter App (UI Only)

Module 5: Common Widget In Flutter

- Containers and their role.

- Importing images from a network.

- Importing images as assets.

- Adding icons to widgets.

- Understanding Row and Column.

- ListView and ListTile.

- Building views using ListView.builder.

- Inkwell and its importance.

Module 6: Stateless And Stateful Widgets- The Concept

- Stateless vs. Stateful widgets.

- Defining a State

- The setState() method.

- Returning to the Default Flutter App.

Module 7: Navigating Through Navigation

- Navigator and routes.

- Applying push() using MaterialPageRoute.

- Applying pop().

- Declaring parameter-less routes (push Named()) in Materia Lapp widget.

Module 8: Handling User Input

- Using Text Field.

- Handling changes to a Text Field.

- Pass retrieved values using Navigator.

Module 9: User Interface

- Applying Theme Data.

- The Basic Screen Layout.

- Applying Custom Font.

Module 10: Asynchronous Functions

- function.

- async and await

Module 11: Working With Remote Data

- The http package.

- Model Class and JSON parsing.

- Displaying Remote Data. (NEWS API).

Module 12: Local storage

- Shared Preferences.

Module 13: Using 3rd Party Packages

- The url_launcher package.

- Adding onTap() to NEWS API.

Module 14: Other Useful Widgets

- Grid View.

- The Hero Animation

- Stack

- Alert Dialog with buttons.

This syllabus is not final and can be customized as per needs/updates

Flutter Course has the potential to be a cross-platform app development solution. A specialist can use the Cupertino library included in the SDK while working on the iOS component.

. By using the tools given by flutter, you can make internationalisation a snap and include it straight into development. You'll learn how to code in Dart and create attractive, quick, native-quality iOS and Android apps throughout this training programme. It's a method of developing an application for all operating systems on a case-by-case basis.

Google designed it using a tiered architecture to produce a UI that is both expressive and adaptable. Nestsoft offers the best Google Flutter training as well as mobile app development courses. As a result, it is more affordable. Learn from our on-site Expert Professionals.

Flutter Course has the potential to be a cross-platform app development solution. A specialist can use the Cupertino library included in the SDK while working on the iOS component.

. By using the tools given by flutter, you can make internationalisation a snap and include it straight into development. You'll learn how to code in Dart and create attractive, quick, native-quality iOS and Android apps throughout this training programme. It's a method of developing an application for all operating systems on a case-by-case basis.

Google designed it using a tiered architecture to produce a UI that is both expressive and adaptable. Nestsoft offers the best Google Flutter training as well as mobile app development courses. As a result, it is more affordable. Learn from our on-site Expert Professionals.