Php/MySQL Training by Experts

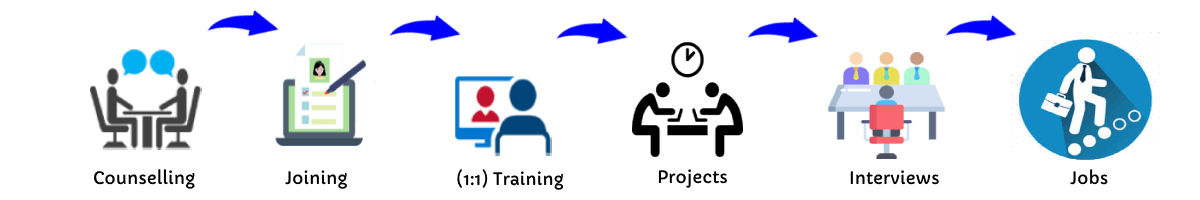

Our Training Process

Php/MySQL - Syllabus, Fees & Duration

Introduction to PHP

- Evaluation of PHP

- Basic syntax

- Defines variable and constant

- PHP Data Type

- Operator and expression

Handles HTML form using PHP

- Capturing form data

- File Multi-Value

- Creates a file uploaded form

- Redirects a form after submission

Decisions and loop

- Making decisions

- Doing repetitive work with looping

- Decisions and Mixing with HTML

Action

- What is an activity?

- Define a function

- Call by value, call by reference

- Repeat action

String

- Creating and accessing the string

- The string is searched and replaced

- Formatting the string

- String related library functionality

Array

- Anatomy of an Array

- Creates an index-based and associative array

- Accessing the array element

- Looping using an index based array

- Looping with associative array with each () and for each ()

- Some useful library activity

Works with files and directories

- Understanding the file and directory

- Opens and closes a file

- Copy, rename, and delete a file

- Working with directories

- Creating a text editor

- File uploading and downloading

The string matches the regular expression

- What is regular expression

- Pattern matching in PHP

- Replacing the text

- Splits a string with a regular expression

Creating images using PHP

- Fundamentals of computer graphics

- Creating the image

- Managing the image

- Using the text in the image

Database connectivity with MySQL

- Introduction to RDBMS

- Connection to MySQL database

- Performing Basic Database Functionality (Insert, Delete, Update, and Select)

- Sets the query parameter

- Implementing the query

- Join (Cross joins, Inner joins, Outer join, Self joins)

Advanced PHP

- Introduction to OOPS

- MySQL database

- Create dynamic pages using PHP and MySQL

- Ajax

- jQuery

HTML 5 (5 Hours)

CSS (5 Hours)

Bootstrap (5 Hours)

Javascript (5 Hours)

This syllabus is not final and can be customized as per needs/updates

However, its market has altered over time, and the PHP coding language is now regarded as one of the most effective and favored programming tools for web development, thanks to several advantages that will be the focus of this essay.

It is regarded as a highly effective technology that provides a convenient development technique as well as various additional instruments to aid it. Our goal is to provide the necessary knowledge and abilities for constructing PHP-based web apps and websites. Because the majority of these frameworks are free to sources, they can be used without paying any license fees. As a responsible business person, you should use powerful programming tools and database management systems. Nestsoft in Toowoomba offers PHP online live training that takes a systematic approach to coach you to become a competent and knowledgeable PHP developer by teaching you all you need to know about HTML5 from the ground up. It is a fantastic and widely spoken language. They also improve the user experience provided by the online application. This online programming language is straightforward to grasp and master, especially for people with a background in C, JavaScript, and HTML.

So, despite its simplicity, PHP is the most extensively used web development language.

However, its market has altered over time, and the PHP coding language is now regarded as one of the most effective and favored programming tools for web development, thanks to several advantages that will be the focus of this essay.

It is regarded as a highly effective technology that provides a convenient development technique as well as various additional instruments to aid it. Our goal is to provide the necessary knowledge and abilities for constructing PHP-based web apps and websites. Because the majority of these frameworks are free to sources, they can be used without paying any license fees. As a responsible business person, you should use powerful programming tools and database management systems. Nestsoft in Toowoomba offers PHP online live training that takes a systematic approach to coach you to become a competent and knowledgeable PHP developer by teaching you all you need to know about HTML5 from the ground up. It is a fantastic and widely spoken language. They also improve the user experience provided by the online application. This online programming language is straightforward to grasp and master, especially for people with a background in C, JavaScript, and HTML.

So, despite its simplicity, PHP is the most extensively used web development language.