ASP.NET MVC Training by Experts

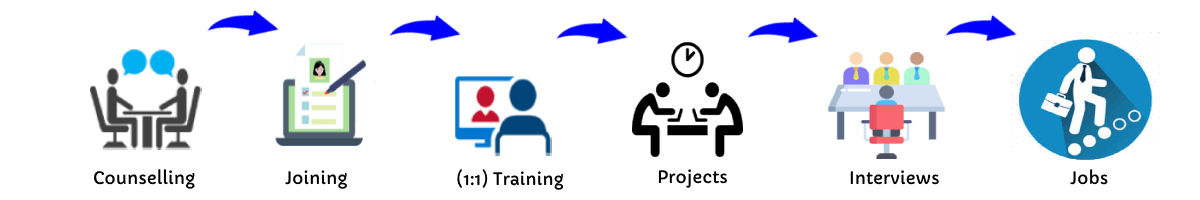

Our Training Process

ASP.NET MVC - Syllabus, Fees & Duration

Section 1 : HTML5

- Introduction and History

- Basic tags and attributes

Section 2 : JavaScript

- Introduction to Javascript

- JS Variables

- JSFunctions

Section 3 : CSS3

- Selectors

- The box model

- Backgrounds and Borders

- Picture

- Text effects

- 2D / Transitions

- Animations

- Multiple layouts

- User Interface

Section 4 : Introduction to Bootstrap

- Bootstrap grid system

- Bootstrap Grid System - Advanced.

Section 5 : SQL

- Introduction to DBMS

- Difference Between DBMS and RDBMS

- SQL controls

- DML and DDL functions

- Groupby, heaving vStored procedure

- Triggers

Section 6 : Web programming ideas

- Introduction to Web Programming

- Client / server technology

Section 7 : .Net Platform

- Explore.net framework 4.5

- Understanding Roll of CTS and CLS

- Learnbase class libraries

Section 8 : Asp.net framework 4.5

- The Net Framework

- Common language

- Frameclass Library

- Waste collection

- MSIL

- The type of websites

- Intrinsic Objects In asp.net

Section 9 : Classes and objects

- Class and objects

- Methods and Properties

- Manufacturers

- Property Procedures

- Numbers

- References. Evaluation

- Structures

- Namespaces

- Dynamic Dynamic Language Range Time

- Abstract class and interfaces

- Exceptions handling.net 4.5

Section 10 : Arrays and Collections

- Array

- Changes the ranges

- ArrayLists and Hashtables

- Public collections

Section 11 : Web Forms

- Web Control Class

- Creating a webform application

- Handling images

- Navigating

- Managing Server Controls

Section 12 : Uploading files

- Using the file upload control

- Restrictions

Section 13 : ADO.NET

- Connection object

- Command object

- Datacredders

- Datasets and Data Adaptors

- Using SQL Datasource

- Forms With DataBase Connectivity

Section 14 : State Management

- Saving Web Applications

- Using Preserve State

- Asp.net session state

- Application State

- Master Pages and themes

- Simple Master Page Nested Master Page

- Configuring MasterPage Creating Themes

- Applicable

- Applying external style

- Working With Template

Section 15 : Database connection with different architecture

- Two column architecture

- Three-dimensional architecture

- Working With the Procedure

- FileI / O and streams

- Working With directories and Files Read and write file

Section 16 : Xml

- The basics of XML

- Create XML document

- XML reader and XML Writer

- XML Data Binding

- XML Data Source Control

Section 17 : Linq

- Linq Introduction

- LINQ to SQL

- Linq to Dataset

- LINQ to XML

Section 18 : User Controls

- Creating UserControls

- Interacting seed sir controls

- Loading User Controls Dynamically

Section 19 : ASP.NET Web Services

- Introduction to XML Web Services

- Creating a web service

- Setting the Web Service attribute

- Testandrunyourweb service

- Consumer consumer service in client application

Section 20 : Ajax

- Understanding Ajax Controls

- How Ajax works

- Ajax Server Controls

- Downloading and Installing the Ajax Control Toolkit

- Creating an ASPX Page with Ajax

Section 21 : jQuery

- Introduction to jQuery

- jQuery effects

- jQuery html

- Query ajax

- Examples

Section 22 : IIS 7

- Architecture of IIS7

- IIS Manager

- Publishing the web application

Section 23 : MVC

- Introduction to MVC

- MVC Application

- MVC folders

- Adding Controller

- Adding sight

- Adding a model

This syllabus is not final and can be customized as per needs/updates

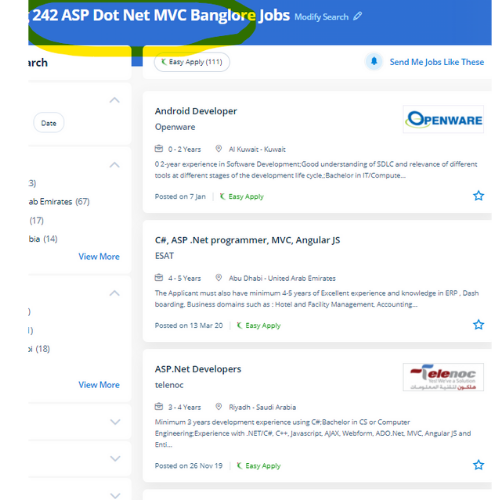

NET MVC brings faster performance on the client-side as well as within the development process. With fast changes to the most recent user interface and usability across different business domains, it is inevitable to have complete control over hypertext markup language therefore corresponding forepart parts will be enforced with ease and altered without much overhead over the quantity of time. Our certification educational program in the ASP. most significantly, since MVC may be a cleaner, systematic, and a lot of advanced manner of implementing structured growth of software it is terribly acceptable for firms that are running enterprise applications that involve a quality side, There are several PHP frameworks like Yii and Zend which provide MVC based implementation and with ASP. Net MVC framework, it provides identical leverage to Microsoft technologies. Overall application performance are dramatically increased by just-in-time compilation, good caching technologies, and native optimization. NET allows the server to make effective web pages. Asp . this will increase overall development speed and cut back development prices for ASP. Nestsoft is one of the most effective ASP.

NET MVC brings faster performance on the client-side as well as within the development process. With fast changes to the most recent user interface and usability across different business domains, it is inevitable to have complete control over hypertext markup language therefore corresponding forepart parts will be enforced with ease and altered without much overhead over the quantity of time. Our certification educational program in the ASP. most significantly, since MVC may be a cleaner, systematic, and a lot of advanced manner of implementing structured growth of software it is terribly acceptable for firms that are running enterprise applications that involve a quality side, There are several PHP frameworks like Yii and Zend which provide MVC based implementation and with ASP. Net MVC framework, it provides identical leverage to Microsoft technologies. Overall application performance are dramatically increased by just-in-time compilation, good caching technologies, and native optimization. NET allows the server to make effective web pages. Asp . this will increase overall development speed and cut back development prices for ASP. Nestsoft is one of the most effective ASP.