iOS Training by Experts

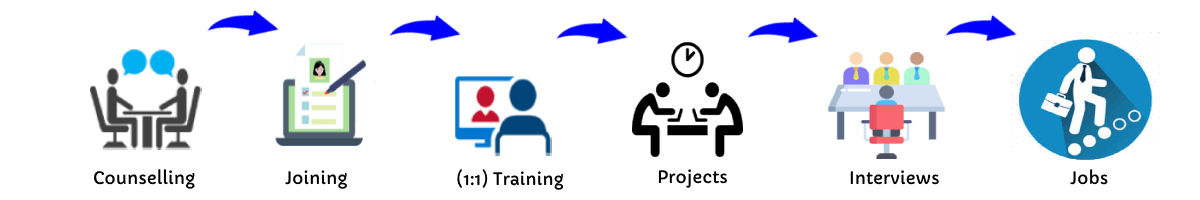

Our Training Process

iOS - Syllabus, Fees & Duration

-

iOS Development Environment

- Introduction to iOS SDK

- What’s new in iOS9

- SDK Tools

- What’s new in Xcode7

- Using XCode

- Using Interface Builder

- Using iPhone Simulator

-

Swift Language Basics

- Core Data Types

- String Type

- Tuples & Optional

- Constants & Variables

- Statements & Operators

- Control Flow & Decisions

- Functions

-

Basic Object Oriented Programming using Swift

- Structs

- Types versus instances

- Member and static methods

- Custom initialization & De-initialization

- Classes

- Initialization

- Methods

- Properties

-

Advanced Object Oriented Programming using Swift

- Optional

- Introducing optional

- Unwrapping an optional

- Optional binding

- Nested Types

- Generic Types

- Protocol

- Optional

-

Memory Management

- Reference Counting Basics

- Automatic Reference Count

- Retain Cycles

-

iPhone Application Basics

- Anatomy of an iPhone application

- Application Lifecycle and States

-

User Interface Programming– Basics

- UI Kit Framework

- XIB and Interface Builder

- Window & View

- Basic User Controls

- Labels, Text Fields, Buttons, Sliders, Picker etc.

- Building application screens

- Alerts and Action Sheets

-

Auto-layout and Constraints

-

View Controllers

- Basics

- Creating View Controllers

- Content vs Container View Controllers

- Orientation Management

-

User Interface– Special Views

- Image View

- Scroll View

- Table Views

- Populating and configuring Table View

- Data Source and Delegate

- Table View Cells

- Custom Cells

- Editing Table View

- Collection View

-

Multiple View Controllers

- Applications with Multiple Views

- Presenting View Controllers

- Animating View Switching

-

Storyboards

- Storyboard File

- View Controller and Scene

- Segue

- Invoking a Segue

- XIB and Storyboards

- Table View Cell Prototype

-

Multi Touch and Gestures API

-

Data Persistence - 1

- File System

- SQLite

-

Data Persistence - 2

- Core Data

- NS User Defaults

-

Concurrency and Background Execution

- GCD and Closures

- NS Operation and NS Operation Queue

- Background execution

-

Networking, Connectivity

-

Multimedia

This syllabus is not final and can be customized as per needs/updates

Our instructor has over ten years of experience working in MNCs in the fields of iOS App Development and related technologies. The design of iOS is based on the UNIX and Mac OS operating systems, and it allows for direct interaction such as touch, swipes, and other gestures. We designed our curriculum to align with real-world requirements at all levels, from beginner to advance. Additionally, iOS has a layered architecture.

Every iOS app runs well on an iPhone, giving a great user experience that is typically required for a business.

We are the best coaching institute in an area that provides certification-focused IOS training.

. Because of the unique features and support it provides to its clients, Apple iOS has maintained its dominance in the smartphone sector. iOS is a mobile operating system developed by Apple specifically for its iPhone and iPad devices. You are a brilliant app developer because of your extensive expertise and constant monitoring.

Our instructor has over ten years of experience working in MNCs in the fields of iOS App Development and related technologies. The design of iOS is based on the UNIX and Mac OS operating systems, and it allows for direct interaction such as touch, swipes, and other gestures. We designed our curriculum to align with real-world requirements at all levels, from beginner to advance. Additionally, iOS has a layered architecture.

Every iOS app runs well on an iPhone, giving a great user experience that is typically required for a business.

We are the best coaching institute in an area that provides certification-focused IOS training.

. Because of the unique features and support it provides to its clients, Apple iOS has maintained its dominance in the smartphone sector. iOS is a mobile operating system developed by Apple specifically for its iPhone and iPad devices. You are a brilliant app developer because of your extensive expertise and constant monitoring.