R Programming Training by Experts

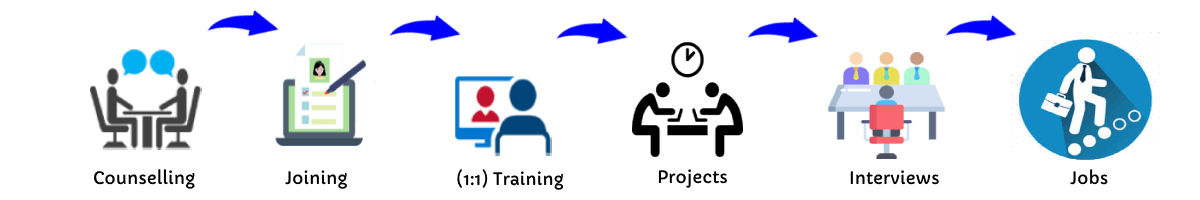

Our Training Process

R Programming - Syllabus, Fees & Duration

THE ART OF R PROGRAMMING

- Why Use R for Your Statistical Work?

- Object-Oriented Programming

- Functional Programming?

- Functional Programming?

- Downloading R from CRAN

- Installing from Source

- Interactive Mode

- Batch Mode

- Variable Scope

- Default Arguments

- Vectors, the R

- Character Strings

- Matrices

- Lists

- Arrays

- Data Frames

- Adding and Deleting Vector Elements

- Obtaining the Length of a Vector

- Matrices and Arrays as Vectors

- Vector Arithmetic and Logical Operations

- Vector Indexing

- Generating Useful Vectors with the : Operator

- Generating Vector Sequences with seq()

- Repeating Vector Constants with rep

- Vector In, Vector Out

- Vector In, Matrix Out

- Using NA

- Using NULL

- Generating Filtering Indices

- Filtering with the subset() Function

- The Selection Function which

- Extended Example: A Measure of Association

- Extended Example: Recoding an Abalone Data Set

- General Matrix Operations

- Performing Linear Algebra Operations on Matrices

- Matrix Indexing

- Filtering on Matrices

- Using the apply() Function

- Extended Example: Finding Outliers

- Adding and Deleting Matrix Rows and Columns

- Changing the Size of a Matrix

- List Indexing

- Adding and Deleting List Elements

- Getting the Size of a List

- Using the lapply() and sapply() Functions

- Naming Columns and Rows

- Accessing Array Elements

- Check if an Item Exists

- Amount of Rows and Columns

- Array Length

- Manipulating Array Elements

- Calculations Across Array Elements

- Accessing Data Frames

- Extracting Subdata Frames

- More on Treatment of NA Values

- Using the rbind() and cbind() Functions and Alternatives .

- Applying apply()

- Extended Example: An Employee Database

- Using lapply() and sapply() on Data Frames

- The tapply() Function

- The split() Function

- The by() Function

- Matrix/Array-Like Operations on Tables

- Extended Example: Extracting a

- The aggregate() Function

- The cut() Function

- Loops

- Looping Over Non vector Sets if-else

- Deciding Whether to Explicitly Call return()

- Returning Complex Objects

- The Scope Hierarchy

- More on ls()

- Functions Have (Almost) No Side Effects

- Writing to Nonlocals with the Super assignment Operator

- Writing to Nonlocals with assign()

- What’s Considered a Replacement Function?

- Text Editors and Integrated Development Environments

- Extended Example

- Cumulative Sums and Products

- Minima and Maxima

- Extended Example: Vector Cross Product

- Set Operations

- Built-In Random Variate Generators

- Obtaining the Same Random Stream in Repeated Runs

- Using the scan() Function

- Using the readline() Function

- Printing to the Screen

- Reading a Data Frame or Matrix from a File

- Reading Text Files

- Introduction to Connections

- Extended Example

- Accessing Files on Remote Machines via URLs

- Writing to a File

- Getting File and Directory Information

- grep()

- nchar()

- paste()

- sprintf()

- substr

- strsplit()

- regexpr()

- Extended Example

- Reading a CSV File

- Analyzing the CSV File

- Writing into a CSV File

- Install xlsx Package

- Reading the Excel File

- Writing the Binary File

- Reading the Binary File

- Reading XML File

- XML to Data Frame

- Install rjson Package

- Read the JSON File

- Convert JSON to a Data Frame

- RMySQL Package

- Connecting R to MySql

- Querying the Tables

- Query with Filter Clause

- Updating Rows in the Tables

- Inserting Data into the Tables

- Creating Tables in MySql

- Dropping Tables in MySql

- The Workhorse of R Base Graphics: The plot() Function

- R - Pie Charts

- R - Bar Charts

- R - Boxplots

- R - Histograms

- R - Line Graphs

- R - Scatterplots

- Starting a New Graph While Keeping the Old Ones

- Extended Example

- Adding Points: The points() Function

- Adding a Legend: The legend() Function

- Adding Text: The text() Function

- Pinpointing Locations: The locator() Function

- Restoring a Plot

- Customizing Graphs

- Changing Character Sizes: The cex

- Changing the Range of Axes: The xlim and ylim Options

- Graphing Explicit Functions

- Extended Example

- R Graphics Devices

- Saving the Displayed Graph

- Closing an R Graphics Device

INTRODUCTION

INSTALLING R

GETTING STARTED

How to Run R

First R Session

Introduction to Functions

Preview of Some Important R Data Structures

VECTORS

Scalars, Vectors, Arrays, and Matrices

Declarations

Common Vector Operations

Vectorized Operations

NA and NULL Values

Filtering

A Vectorized if-then-else: The ifelse() Function

Testing Vector Equality

Vector Element Names

More on c()

MATRICES AND ARRAYS

Creating Matrices

Applying Functions to Matrix Rows and Columns

More on the Vector/Matrix Distinction

Avoiding Unintended Dimension Reduction

Naming Matrix Rows and Columns

Higher-Dimensional Arrays

LISTS

Creating Lists

General List Operations

Accessing List Components and Values

Applying Functions to Lists

ARRAYS

DATA FRAMES

Creating Data Frames

Other Matrix-Like Operations

Merging Data Frames

Applying Functions to Data Frames

FACTORS AND TABLES

Factors and Levels

Common Functions Used with Factors

Working with Tables

Other Factor- and Table-Related Functions

R PROGRAMMING STRUCTURES

Control Statements

Arithmetic and Boolean Operators and Values

Default Values for Arguments

Return Values

Functions Are Objects

Environment and Scope Issues

The Top-Level Environment

No Pointers in R

Writing Upstairs

When Should You Use Global Variables?

Replacement Functions

Tools for Composing Function Code

The edit() Function

Writing Your Own Binary Operations

Anonymous Functions

DOING MATH AND SIMULATIONS IN R

Math Functions

Functions for Statistical Distributions

Sorting

Linear Algebra Operations on Vectors and Matrices

Simulation Programming in R

INPUT/OUTPUT

Accessing the Keyboard and Monitor

Reading and Writing Files

STRING MANIPULATION

An Overview of String-Manipulation Functions

Regular Expressions

R DATA INTERFACES

R - CSV Files

R - Excel Files

R - Binary Files

R - XML Files

R - JSON Files

R - Database

GRAPHICS

Creating Graphs

Saving Graphs to Files

Creating Three-Dimensional Plots

R Statistics

R Statistics Intro

R Data Set

R Max and Min

R Mean Median Mode

R Percentiles

INSTALLING AND USING PACKAGES

Package Basics

Loading a Package from Your Hard Drive

Downloading a Package from the Web

Installing Packages Automatically

Installing Packages Manually

Listing the Functions in a Package

This syllabus is not final and can be customized as per needs/updates

The course is designed with statistics students in consideration. While teaching R Programming in the classroom, our Nestsoft trainers discuss their previous and current project experiences with candidates, allowing them to gain exposure to real-world business experience.

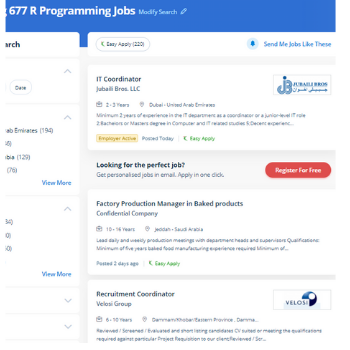

. Students and working professionals can enrol in our top online R Programming training and learn from industry experts who have extensive experience in R Programming advising and R Programming training in Kerala. With the help of R programming, massive datasets may be analysed in less time. We offer training who do not have a background in statistics. Because of its open source credibility, R programming is quickly becoming most in expert in the field of analytics. The course provides students hands-on experience with a variety of R programming principles. We train skilled experts how to use the R programming language in statistical analysis, data visualisation, machine learning, and data mining, among other things. In R, there are a variety of great packages that can aid in a fast data analysis.

The course is designed with statistics students in consideration. While teaching R Programming in the classroom, our Nestsoft trainers discuss their previous and current project experiences with candidates, allowing them to gain exposure to real-world business experience.

. Students and working professionals can enrol in our top online R Programming training and learn from industry experts who have extensive experience in R Programming advising and R Programming training in Kerala. With the help of R programming, massive datasets may be analysed in less time. We offer training who do not have a background in statistics. Because of its open source credibility, R programming is quickly becoming most in expert in the field of analytics. The course provides students hands-on experience with a variety of R programming principles. We train skilled experts how to use the R programming language in statistical analysis, data visualisation, machine learning, and data mining, among other things. In R, there are a variety of great packages that can aid in a fast data analysis.