Tableau Training by Experts

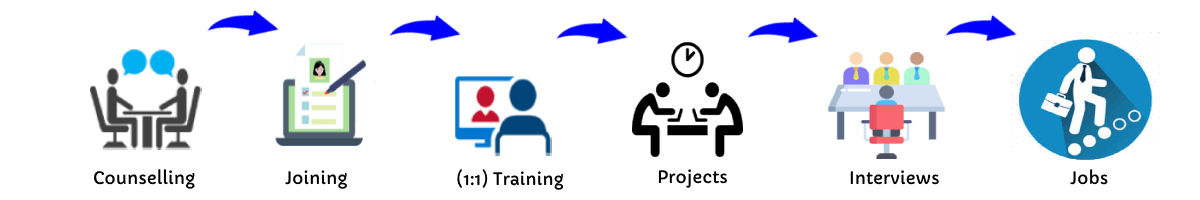

Our Training Process

Tableau - Syllabus, Fees & Duration

Module 1 - What Is Data Visualization?

- Why Visualization came into Picture?

- Importance of Visualizing Data

- Poor Visualizations Vs. Perfect Visualizations

- Principles of Visualizations

- Tufte’s Graphical Integrity Rule

- Tufte’s Principles for Analytical Design

- Visual Rhetoric

- Goal of Data Visualization

Module 2 - Tableau – Data Visualization Tool

- What is Tableau? Different Products and their functioning

- Architecture Of Tableau

- Pivot Tables

- Split Tables

- Hiding

- Rename and Aliases

Module 3 - Tableau User Interface

- Understanding about Data Types and Visual Cues

Module 4 - Basic Chart Types

- Text Tables, Highlight Tables, Heat Map

- Pie Chart, Tree Chart

- Bar Charts, Circle Charts

Module 5 - Intermediate Chart

- Time Series Charts

- Time Series Hands-On

- Dual Lines

- Dual Combination

Module 6 - Advanced Charts

Module 7 - Maps In Tableau

- Types of Maps in Tableau

- Polygon Maps

- Connecting with WMS Server

- Custom Geo coding

Module 8 - Adding Background Image

Module 9 - Data Connectivity In-Depth Understanding

Module 10 - Creating Calculated Fields

Module 11 - Responsive Tool Tips

- Dashboards

Module 12 - Connecting Tableau With Tableau Server

Module 13 - Connecting Tableau With R

This syllabus is not final and can be customized as per needs/updates

Tableau is one of the most popular data visualization solutions for data science and business intelligence requirements.

. The case studies described near the end will only serve to strengthen your understanding and prepare you to handle real-world tasks and difficulties with Tableau. Understanding the tool's essential components and appropriately executing it can help you showcase and deliver data analytics in a lot more polished way. Nestsoft is one of the best of them. The information picked ensures that you fully understand each option. As a company data analyst, you would master the ability to communicate practical consequences, which this course will help you do. After developing a stable platform, this course covers all of Tableau's fundamentals. Most data analytics specialists now consider it a required skill. Certificate holders for various levels of Tableau competence may significantly assist working professionals to gain the competitive edge they need to grab attention.

Tableau is one of the most popular data visualization solutions for data science and business intelligence requirements.

. The case studies described near the end will only serve to strengthen your understanding and prepare you to handle real-world tasks and difficulties with Tableau. Understanding the tool's essential components and appropriately executing it can help you showcase and deliver data analytics in a lot more polished way. Nestsoft is one of the best of them. The information picked ensures that you fully understand each option. As a company data analyst, you would master the ability to communicate practical consequences, which this course will help you do. After developing a stable platform, this course covers all of Tableau's fundamentals. Most data analytics specialists now consider it a required skill. Certificate holders for various levels of Tableau competence may significantly assist working professionals to gain the competitive edge they need to grab attention.